The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) has been predominantly interested in using mouse models to understand human health and disease. In a new study in the journal Conservation Genetics researchers have found another intriguing use of IMPC data.

By comparing genetic functional data from the IMPC with other non-human animals, it may be possible to identify genes relevant for the normal development in those species. For example, by comparing mouse genetic functional data with genomic data for selected species with specific diseases, improved breeding management could be implemented.

To test this potential application researchers at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) and Queen Mary University London (QMUL), alongside colleagues from the IMPC, compared genetic functional data from mice with genomic data from gorillas, showing how such analyses could aid in the identification of genes essential for healthy development.

As well as gorillas, the researchers highlighted other examples, including cheetahs, polar bears, wolves, pandas and cattle. This type of analysis could improve the current management approaches to breeding endangered species, by allowing researchers to identify the matches that are most likely to produce healthy offspring or select breeders to preserve genetic variation relevant for adaptation.

Genes associated with fat metabolism can be a real asset for species like polar bears

Heart disease is a common cause of death for gorillas in captivity and cheetahs suffer from impaired fertility both in captivity and in the wild. By identifying gorilla genes linked to heart disease or cheetah genes linked to infertility, researchers could help better understand the cause for the condition, which is the first step to envisage ways to prevent it. Similarly, this type of data could help identify genes linked to adaptation in certain mammals. For example, genes associated with fat metabolism can be a real asset for species like polar bears, which have diets rich in fats in the extreme environment of the Arctic.

Impaired fertility is common in cheetahs both in captivity and in the wild

“When the number of individuals of a species dramatically decreases, loss of genetic variation also takes place”, explains Violeta Muñoz-Fuentes, Biologist at EMBL-EBI. “This can result in many offspring not surviving, or exhibiting genetic defects linked to fertility or health problems.”

“Many zoos and wildlife conservation centres are seeing excellent results through their breeding programmes. Currently, many focus on minimising inbreeding. By adding a functional genetic dimension to the selective process, conservation geneticists can identify the crosses that would, for example, avoid a gene variant linked to disease in the offspring. It is nevertheless important to keep in mind that for a genetic rescue approach to be successful in the long term, the conditions that led to the decrease of individuals need to be removed; otherwise, the accumulation of deleterious alleles will likely take place again”.

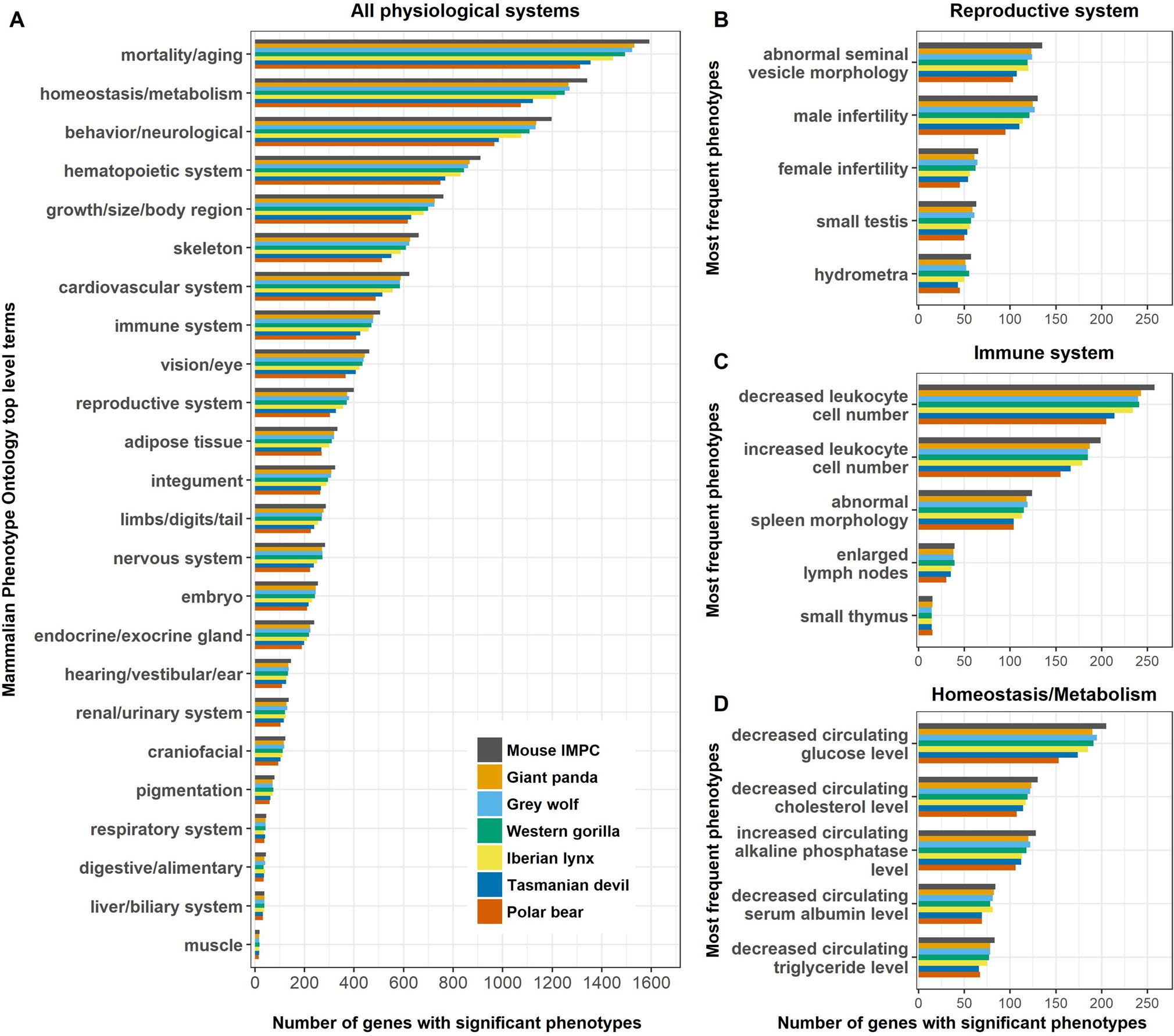

Number of IMPC significant phenotypes for selected mammalian species (source: http://bit.ly/conservationarticle)

Although this type of research is still in its early stages, gene functional knowledge is a powerful tool for maximising adaptive genetic variety within a species and even for reducing genetic variants that negatively affect an individuals’ health and survival. With the accumulation of gene function annotation by the IMPC, as well as technical advancements in gene editing such as CRISPR/Cas9, the hope is that this method of comparing genome information between laboratory mice and endangered wildlife will help in future conservation projects.

The IMPC aims to produce and phenotype knockout mouse lines for 20,000 genes

The IMPC would like to encourage conservation geneticists, conservation centres and zoos to get in touch if they are interested in using IMPC data for conservation purposes.